Blanco

القميص الأبيض

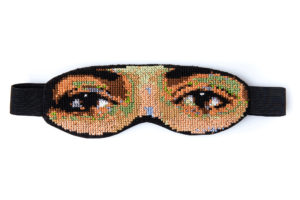

A white shirt is an important part of the universal default aesthetics of well-dressed, reliable, conscious professionals in any situation, whether it is business, politics, universities, talk shows, cultural biennales or cocktail parties. White appears as a ‘neutral’ outfit.

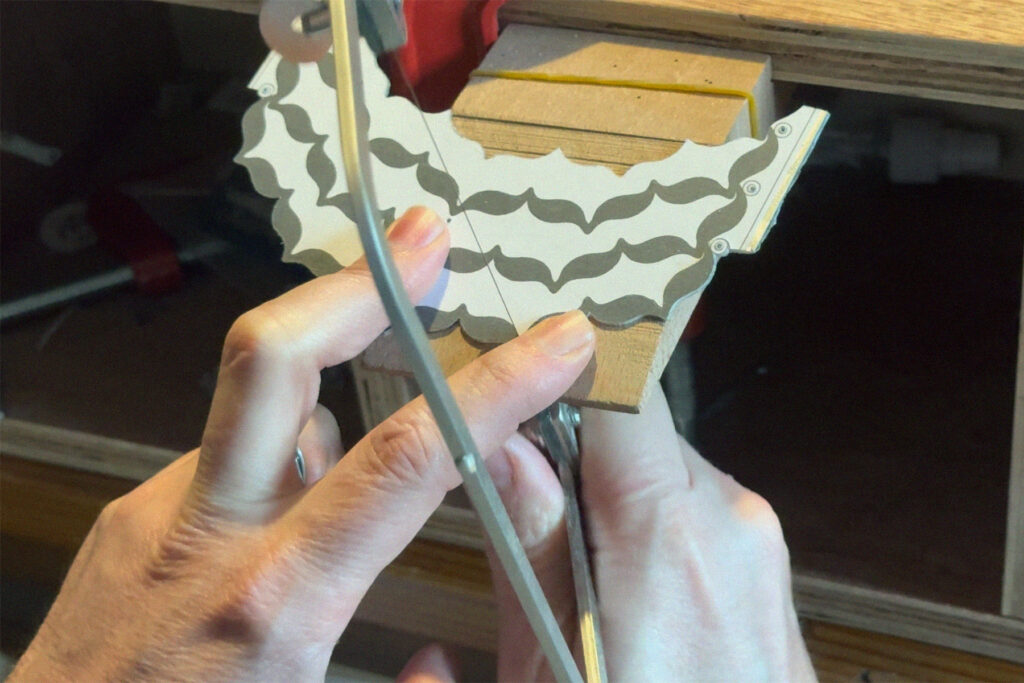

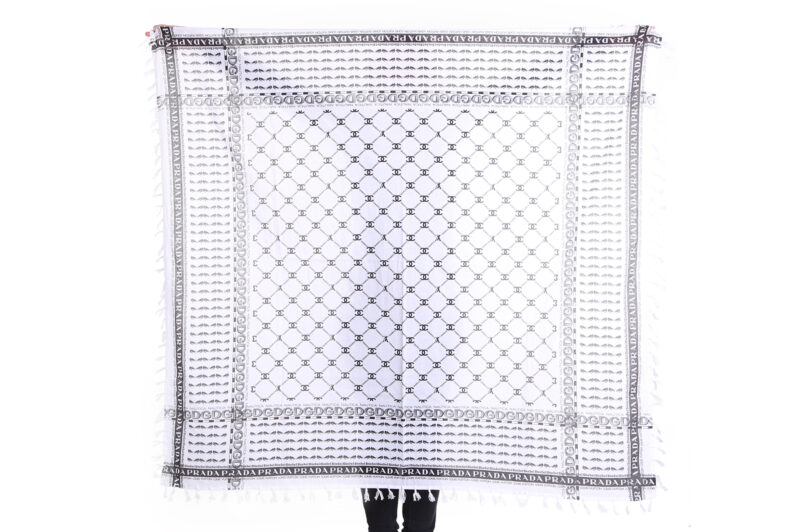

This tailor-made garment is fragile, due to the available machinery and the material. The techniques used to produce it are the same as those used in the traditional keffiyeh, which doesn’t have a ‘blanco’, or blank, neutral, meaning. Indeed, there is no neutrality in situations of oppression. ‘Blanco’ gives you authority because of its social and political symbolism; at the same time, it demands cautious behaviour.

Do not wring.

Do not wear when dirty.

Do not make sudden movements.

Do not bleach.

Do not tumble dry.

Handle with care.

- Tommi Vasko (FI)

Tommi Vasko is a Finish designer based in Amsterdam. He studied at the Sandberg Instituut Amsterdam (Masters Rietveld Academie).

AUTHENTICITY

When a European design student wants to experience authentic night out in Ramallah or in Bethlehem, there are two basic options: one can ask a local to recommend a Palestinian restaurant, order hummus, falafels, shawarma, turkish salad and other local dishes and drink freshly squeezed juice or local Taybeh beer. Or, one can go to one of the restaurants serving non-Palestinian food, drink a Carlsberg or a Coke while a mix of local and western pop-music is playing in the background. While the former option might offer an opportunity to taste the traditional cuisine, it doesn’t mean that the latter would be anyhow less genuine or ‘real’. Nor that one or the other would authentic for all for the same reasons. Or that authenticity would be anyhow objective. So, to be able to conscious about what’s behind this decision, I believe it’s important —at least for me— to examine and open up the notion of authenticity a little bit. On Saturday morning, while one part of the group went to Northern parts of Palestine to see the Qalandiya zoo, I decided to spend the morning walking in the old part of Bethlehem. I came across this arabic market not far from the main square; just a narrow alley and stairs left from the main/oldest street of the city. Narrow alleys with tarps hanging above to provide a bit of shade were crowded already in the morning. Fruit and vegetable stalls, spices, first- and second hand clothing, household stuff, electronics and plastic, basically everything is sold here. Already from far away you could see that most of the things were made in China. The fruits and vegetables however, without labels, rather ripe and unperfect, were certainly cultivated not too far away from here.

If one thinks authenticity as something geographical, something related to soil and the place, the fruits and vegetables in this market had a stronger aura of authenticity than the almost universal made-in-China stuff (it’s more authentic to eat hummus in the middle east than it is in Europe). But at the same time it’s at least as authentic to see Chinese products in the Middle East as it is in Europe.

Later in Ramallah, when the European design student decides to go for a drink to a clean and trendy Mexican restaurant or to hyped Octoberfest in newly opened five star Mövenpick Hotel (or both!), the authenticity is rather cultural. And cultures change. It’s an experience about a moment, people and the global cultural environment. And floating in the Dead sea in lotus position the day after, the experience is again all about the exceptional environment: full-body mud masks and the sea and western pop-music and Nestle ice cream.

- Mark Jan Van Tellingen (NL)

Designer Mark-Jan van Tellingen is an Amsterdam based Dutch designer, who studied at the Sandberg Instituut Amsterdam (Masters Rietveld Academie).

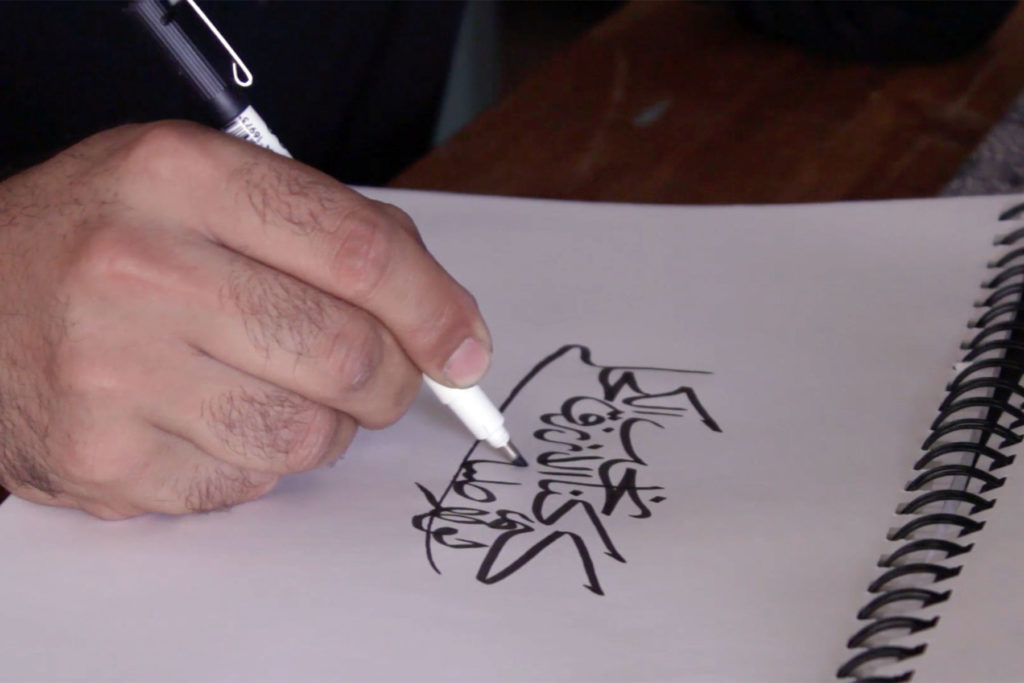

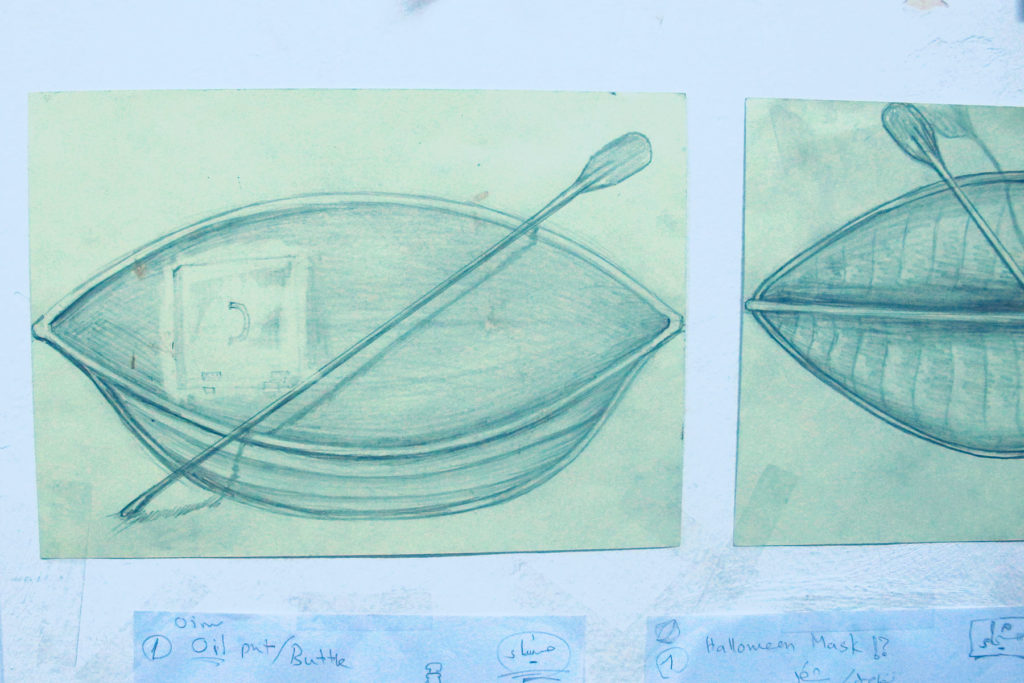

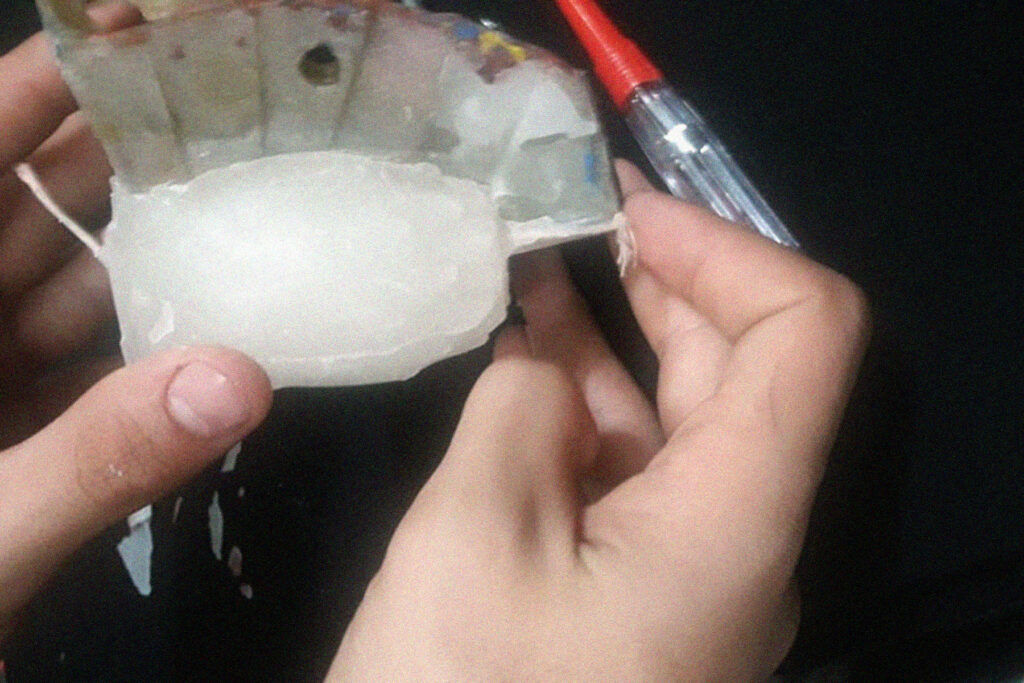

Report of one day during the create-shop 2013: RUMBLING MACHINES

Rumbling machines, steady hands, and hospitality would summarize todays Wonderland. After half an hour drive we arrived in Hebron were we would spend most of our day. When entering the city a warning sign welcomed us ‘No entry for Israelis, entry illegal by israeli law’, as if it was Area 51. In Hebron, the biggest city in Palestine considering the 170.000 inhabitants of H1 and H2, our first stop would be the ceramic and glass workshop. After a quick tour we wandered around the place, admiring the craftsmen that were blowing glass and gracefully decorating pottery. The ease with which they made their glass products was fascinating to see. With the options in mind some of us started painting or collecting ideas for possible products. Several tourists and interested people entered the workshop on and off and were shown around, for a while making it look like an artisan showroom. Our next stop was The Hirbawi Keffiyeh Factory “Raise your keffiyeh, Raise it” as Arab Idol winner Mohammed Assaf sings in “Ali Keffiyeh”. The rumbling sounds of weaving machines slowly came towards us when entering the factory. In the entrance hall a big bedouin tent was implemented as a business meeting point. Two man were keeping a close eye on the keffiyeh during the manufacturing process, removing the threads that were superfluous. The factory, operational since 1961, annually produced 150.000 scarfs until the early 1990s. “Today, due to the signing of the 1993 Oslo Accords and the opening of trade with the outside world, only four machines remain in operation producing a mere 10,000 scarves a year. Not one of these scarves are exported, as overseas suppliers produce mass quantities at a fraction of the price, and the shrinking Palestinian economy and Israeli checkpoints and roadblocks create further hindrances to production and trade for small businesses like Mr. Hirbawi’s. In Mr. Hirbawi’s own words: My machines are in good shape. They can start working tomorrow. I just need a market.”

In the office factory several keffiyehs were bought either for personal use or for artistic purposes. After we filled our bags with the Palestinian symbol of all symbols, Maher Shaheen — one of the participants — invited us to his house for a tea and a sweet arabic coffee. It was a perfect closure of the day being invited into the intimacy of a palestinian family.

- Hirbawi Textile Factory (PS)

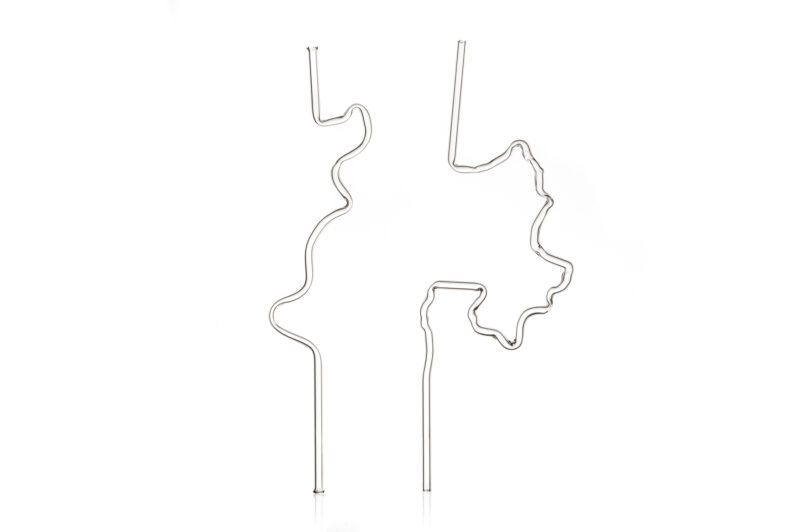

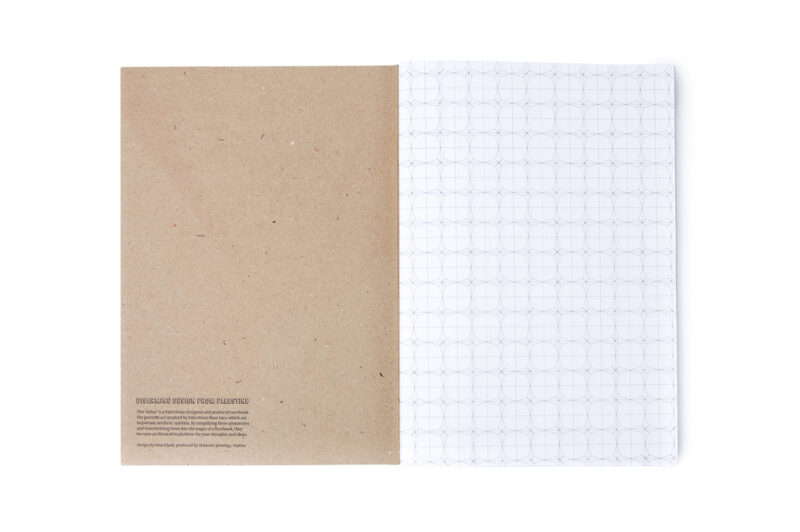

Yasser Hirbawi opened the Hirbawi Textile Factory in 1961 in Hebron, operating 15 machines and producing 150,000 keffiyehs annually by the early 1990s. Today, due to the signing of the 1993 Oslo Accords and the opening of trade with the outside world, only four machines remain in operation producing a mere 10,000 scarves a year. Not one of these scarves are exported, as overseas suppliers produce mass quantities at a fraction of the price, and the shrinking Palestinian economy and Israeli checkpoints and roadblocks create further hindrances to production and trade for small businesses like Mr. Hirbawi’s. In Mr. Hirbawi’s own words: “My machines are in good shape. They can start working tomorrow. I just need a market.” The Keffiyeh’s black and white pattern has come to symbolize the Palestinian struggle; the middle pattern, with its “wire mesh fence” design represents the Israeli occupation, while the oblong-shaped patterns on the side represent olive leaves- a symbol of Palestine and peace.

- Faraj Kasbary (PS)

Faraj Kasbary is a tailor based in Bethlehem.

2013

White Keffiyeh, Olive wood buttons

S, M, L

€75,00