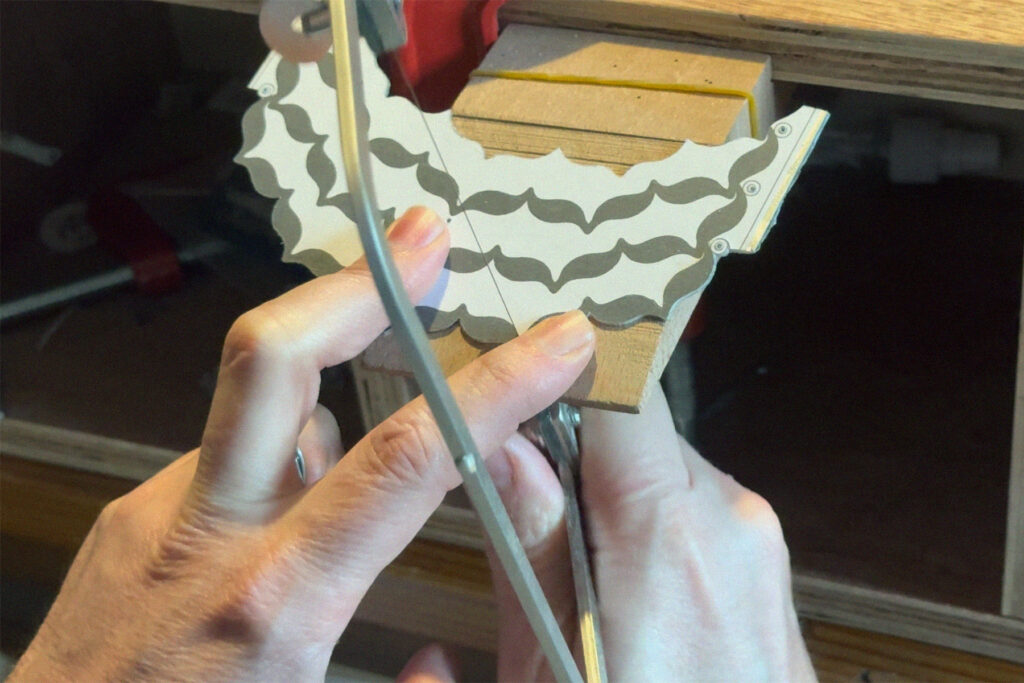

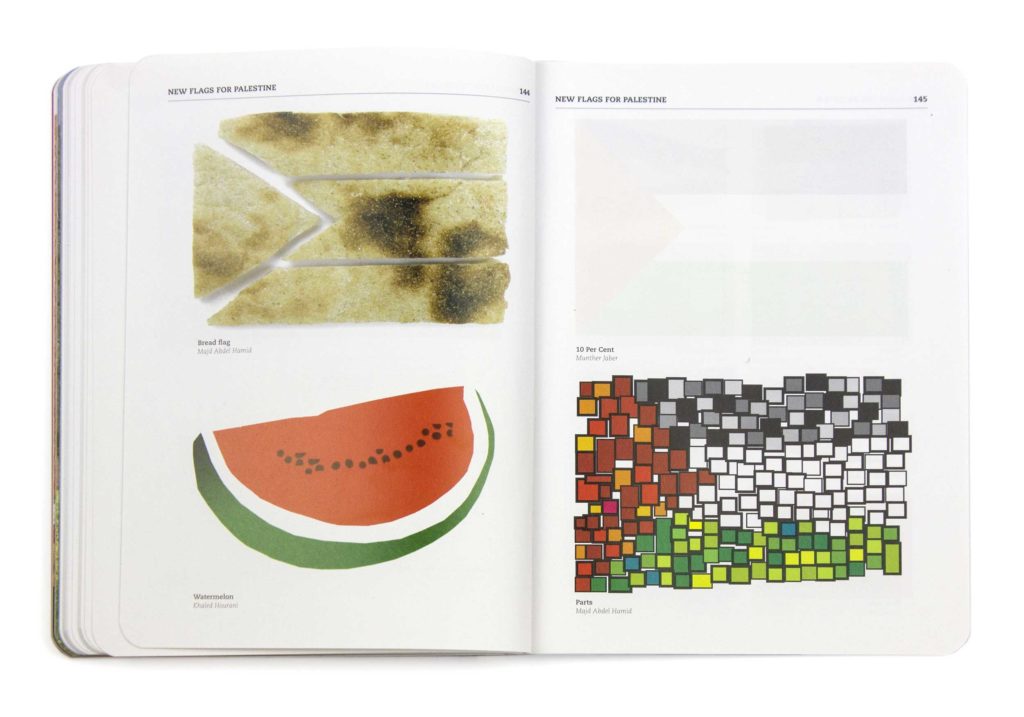

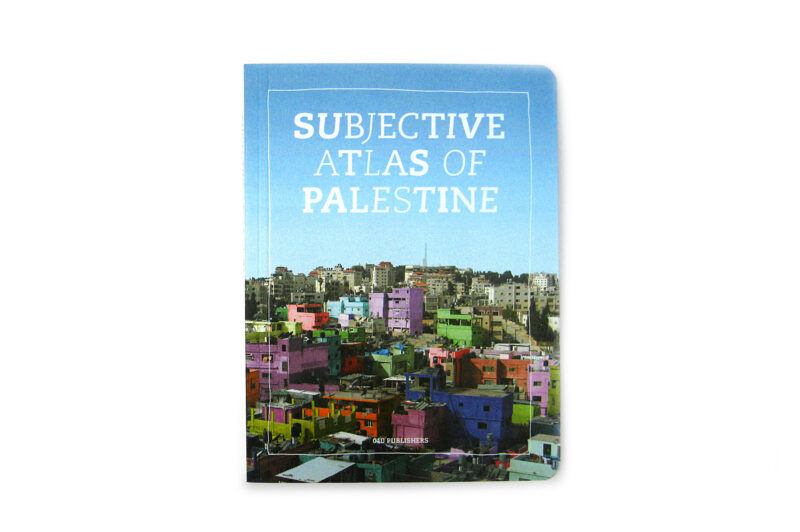

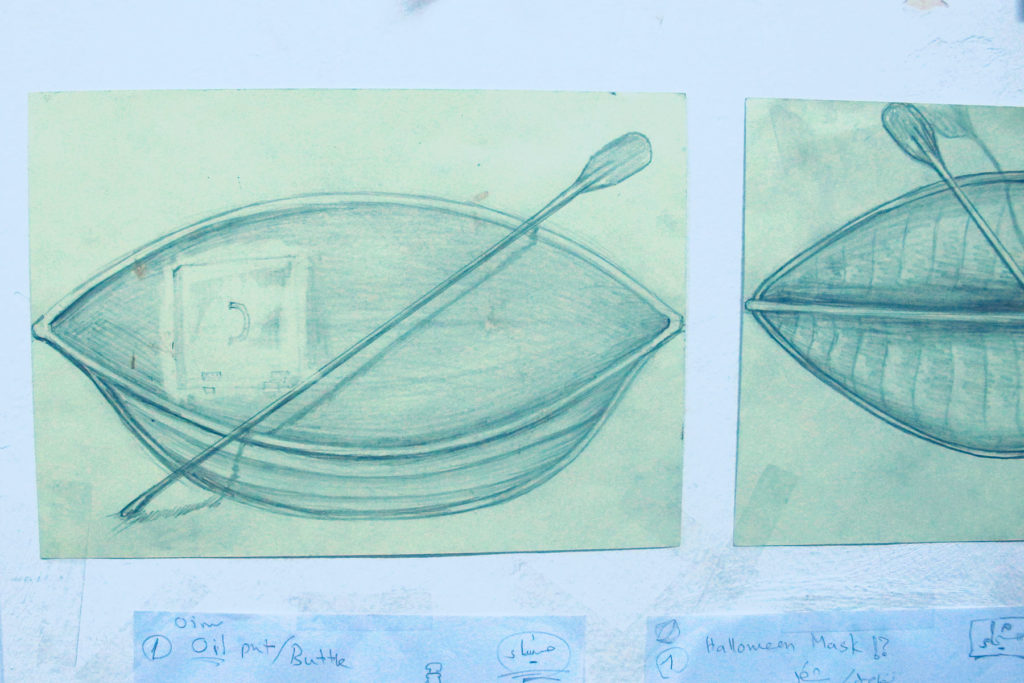

Carpenter Birzeit and designer Ghadeer Dajani, summer 2019

Craftsmanship & materiality

Last summer, with the create-shop, we visited a wood work- shop near Ramallah in the occupied West bank, where the carpenter proudly showed us examples of the complicated and admirable woodwork he used to make for his clients. He explained that customers hardly ask for this skilled work of his anymore as they either find it too expensive or fail to understand the urgency of it – neither do they see the quality. And so, the demand for this competent labour is reducing, with orders becoming less specific, questions more generic, making it harder (and less joyful) for artisans to compete with machines and mass production.

The artisan explained how economically fragile his position was and admitted he didn’t know how long he would be able to keep his workshop open in this manner. Leading him to question how much longer his specific knowledge will be kept alive; acknowledge that is passed down through different generations, and entangled in social structures. Are there new generations that will follow on? If his clients could better understand the relationship between local productions and the knowledge and social structures itempowers, would that change their orders?

These are the indigenous knowledges embodied by craftsmanship, and not something that can be learnt from a book or a YouTube video. lt is the knowledge of generations that goes through the body and is best transmitted in the workshop itself; with the materials, tools, their possibilities and limitations, and with human encounters. In the Netherlands (where I grew up) and in Belgium (where I live) I hardly see artisans at work in cities — those at work often serve a more exclusive market.

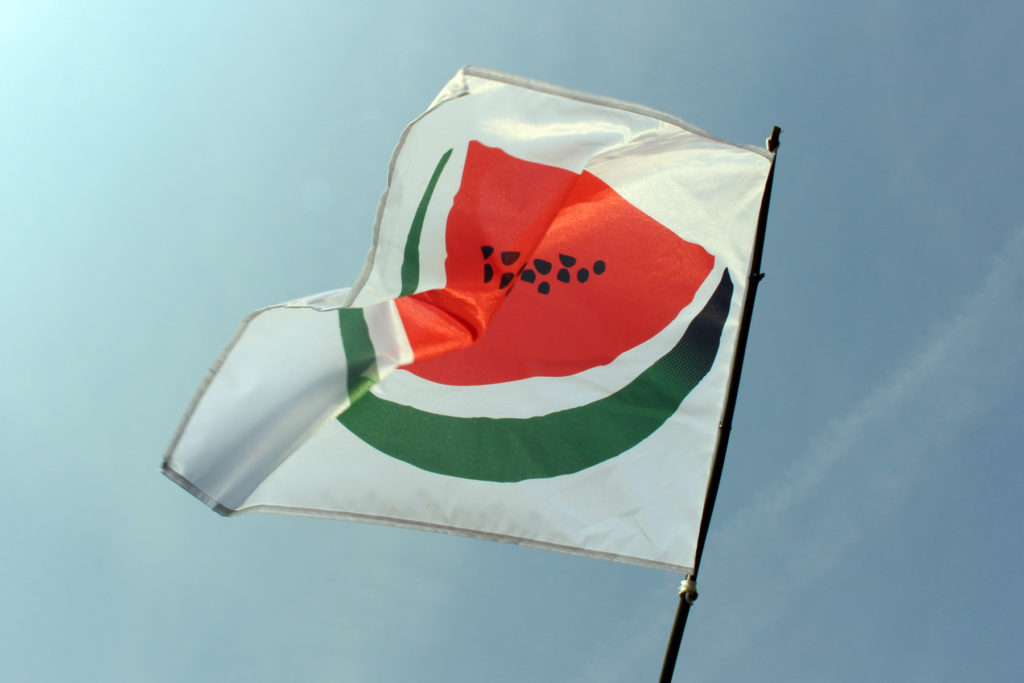

Workshops for wood, metal and leather for instance, are mostly upscaled or have been moved to more industrial areas, or the production is outsourced to low-income-countries. Our dependence on the global market of production has become even more clear during the corona crisis, which fueled a call for local small-scale production. While in the center of cities such as Ramallah, Nablus and Jerusalem one can still (although notably less and less) find several small workshops as part of everyday life; molding metal, making shoes or glazing pottery. To me, this was eye opening; to be aware of these production processes and experience them while passing by or entering the shops introduced me to a rich cultural heritage and made me better understand the social structures that surrounded them, how families are connected, how complicated it can be to transport resources or machines in and products out of the country, how so many artisans have faced military raids in their workspaces and more harsh realities. Alongside this it taught me the effects of colonial occupation and how it oppresses every part of daily life, movement, material, law, economy; everything. This was a fundamental experience. To learn about the occupation through materiality allowed me to deeply see the impact of the disrupted socio-politicalsituation.

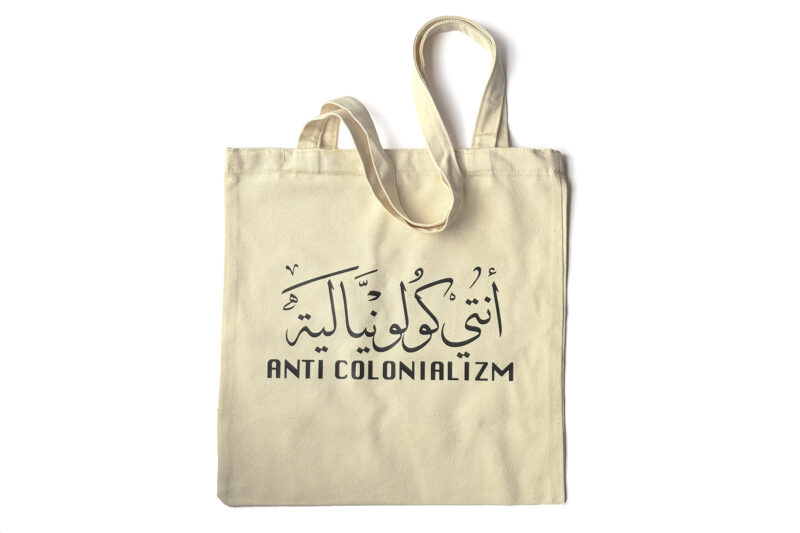

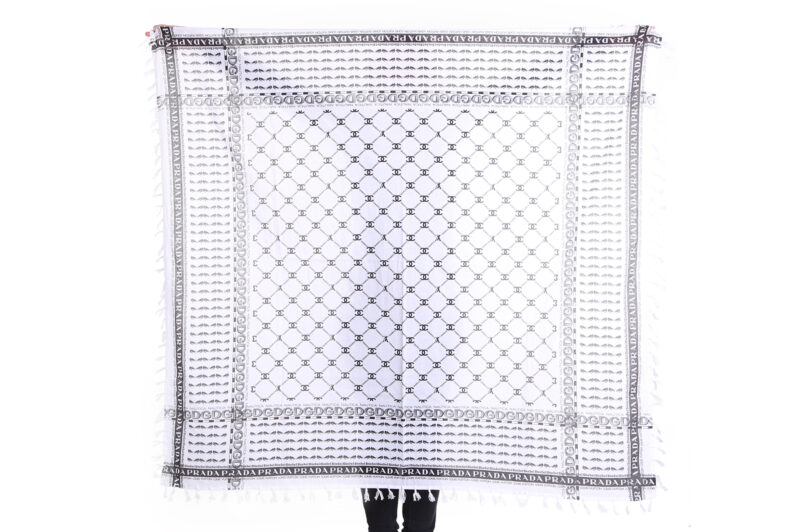

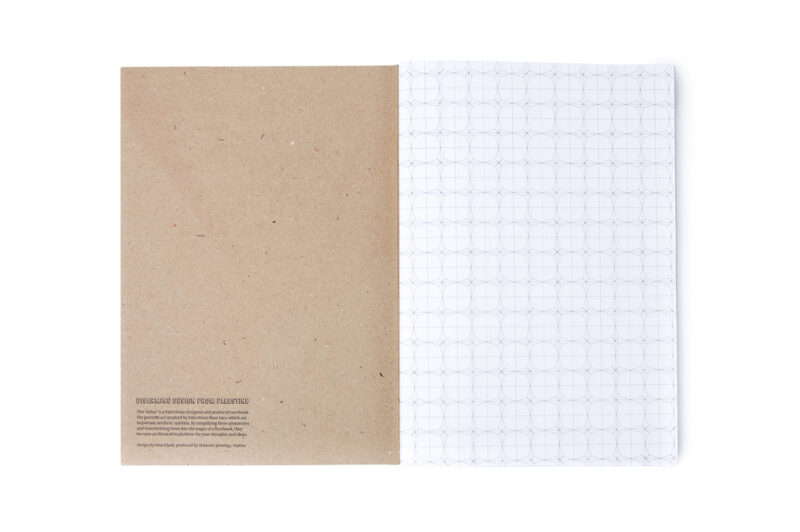

To many, the lsrael-Palestine ‘confict’ emerged mainly from religious or nationalistic issues, while the reality is different because“the occupation is much more related to economic motives within a capitalist ‘game’”, as is explained by Palestinian permaculture designer Mohammad Saleh. The lsraeli economy is directly fed by military technology and security systems, and the private sector plays an explicit role in the Israeli settle- ment enterprise and in the economic exploitation of Palestinian and Syrian land, labour and resources1. As an act of resistance Mohammad Saleh believes it is important to focus on the pro- duction of local designs, especially as a way of acting rather than reacting. “With more local production models, we practice crucial steps of self-sovereignty. It will help artisans to sustain their businesses, families and inherited craftsmanship. This empowers a local economy. The design comes from within and relates to local needs and points of view. This is a socially conscious action, rather than a re-action to the behaviours of others.”

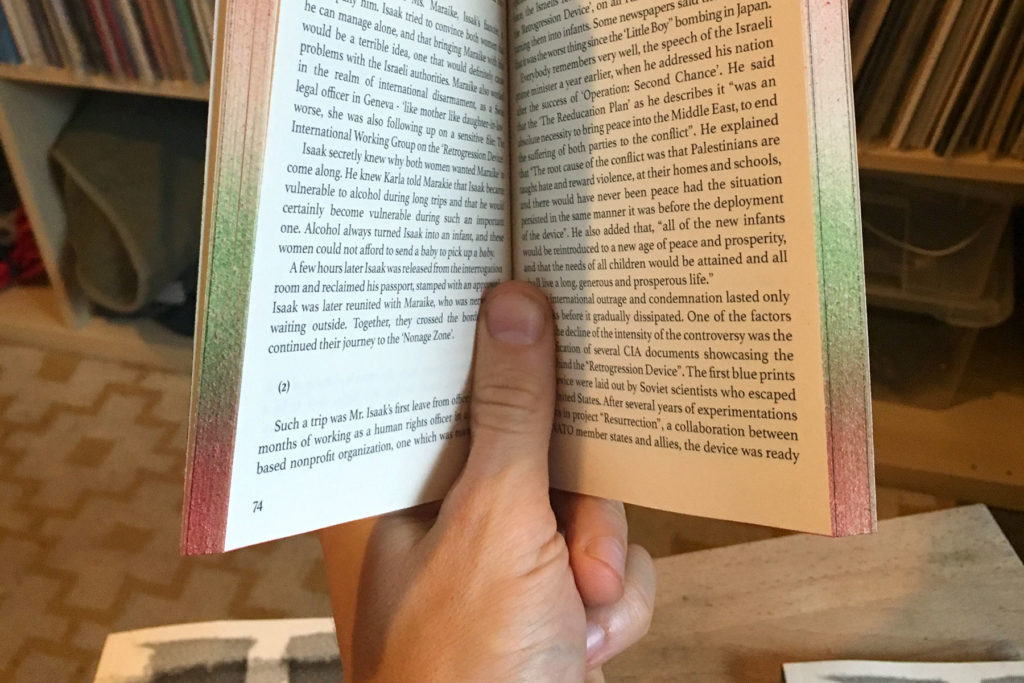

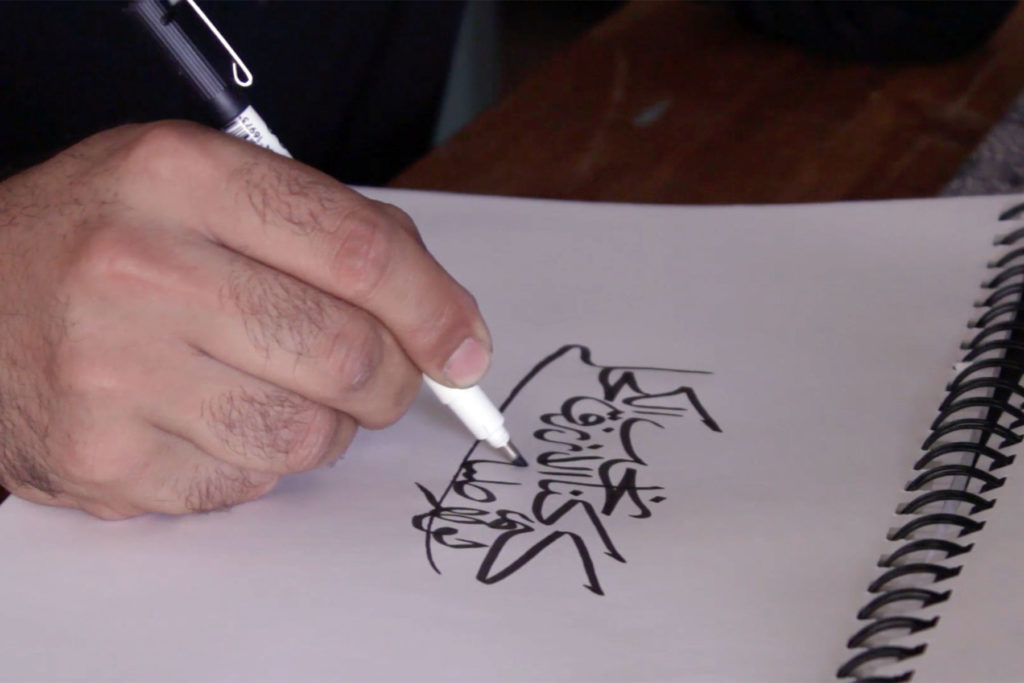

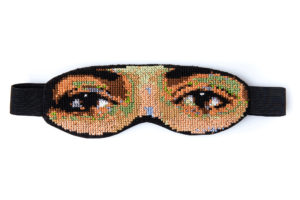

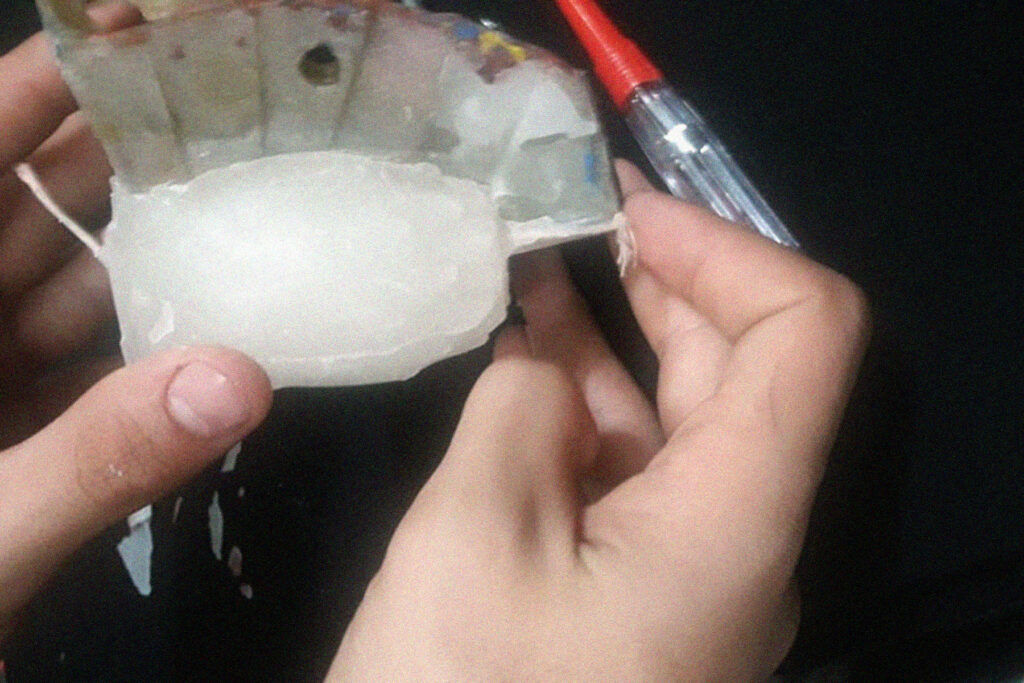

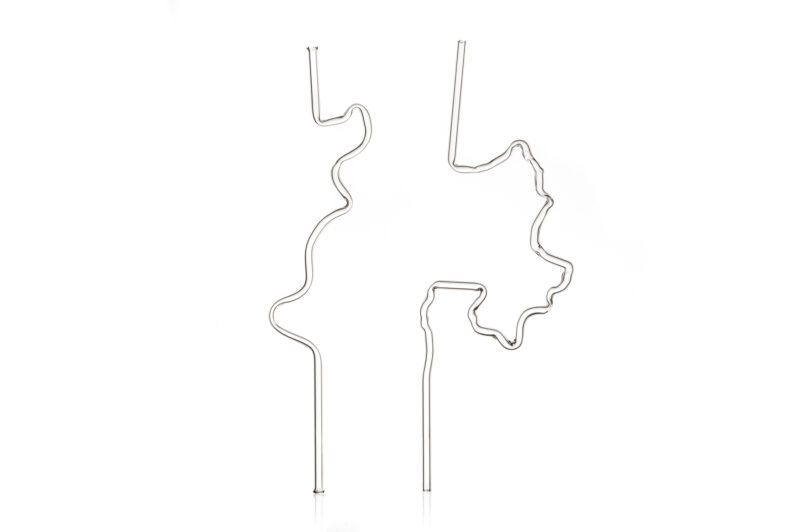

With the create shops that Disarming Design from Palestine organizes, we start the design processes with visiting workshops, meeting artisans and listening to their stories, seeing them at work and trying to understand their mechanisms. Most oftheir knowledge is picked up in practice, in daily life, and not through formal education. As Palestinian designer Qusai Saify explains: „What we learned through working with artisans is to be awake all the time and to be sensitive to each detail you are working on, either how you behave or how you are going to develop the design itself. We live in our heads when we think of a design, but when you really work with the artisans you discover lots of layers. As a designer one can pay attention to the details the artisans are living in and from that you get your feedback to the design itself. If you are aware of this feedback you will learn a lot, if you want to ignore that feedback, or if you are not that sensitive maybe you learn a lot less. Each time something is not working, you need to deal with the situation in a creative way. And with this kind of creativity you don’t have the answer yourself, but you have to find answers together to develop ideas with the artisan. This is a moment when you are reshaping yourself; I felt I was redesigning myself through the designs I was working on.”

Design is a practice of thought and often holds you in a hypothetical individual space behind the computer. When you are working digitally your body often stays more or less in the same position, but when you are making things together your physical movements become part of the energy of the process. Meeting the artisan brings a complete other dimension. Bodies start to interact, you relate to one another, look one another in the eyes, see one’s hands, and feel the materials. This is a relational design process where the body acts in the design development and becomes an important instrument; a tool to make. There is a physical counterforce of the materials and a social interaction between people with very different skill-sets whonormally wouldn’t interact. Often there is a class difference between artisans with lived knowledge and designers from a more formally educated background. They have economic differences, sometimes cultural or racial differences and possibly a language barrier. Visiting the artisan in their working environ- ment places them in the position of strength of knowledge; it puts the skill of crafts and making central to the conversation and allows a mutual space to develop ideas. There is an almost magical exchange taking place in the encounters of testing and making things together; an access to a deeper knowledge, materialized in the acts of making. In doing so, it feels that themoment we better understand how things are made, we achieve a more humane material existence. Making together infuences relationships between people and gives space to mediate initial inequalities, therefore allowing for an emancipatory potential.

These are precognitive processes that go beyond language, beyond a refective attitude and offer participation in different ways. Often in design education the focus is more on aspects of the conceptual, aesthetic or technical, rather than on the role of the body, the sensorial and the design processes that come with it. While this is an important element, even more so when we talk about participative practices and when working with people from different backgrounds. Bodies matter and infuence a sense of trust, connectivity and creativity. It’s something we should take into account, question and sensitize while working together in thesame space.