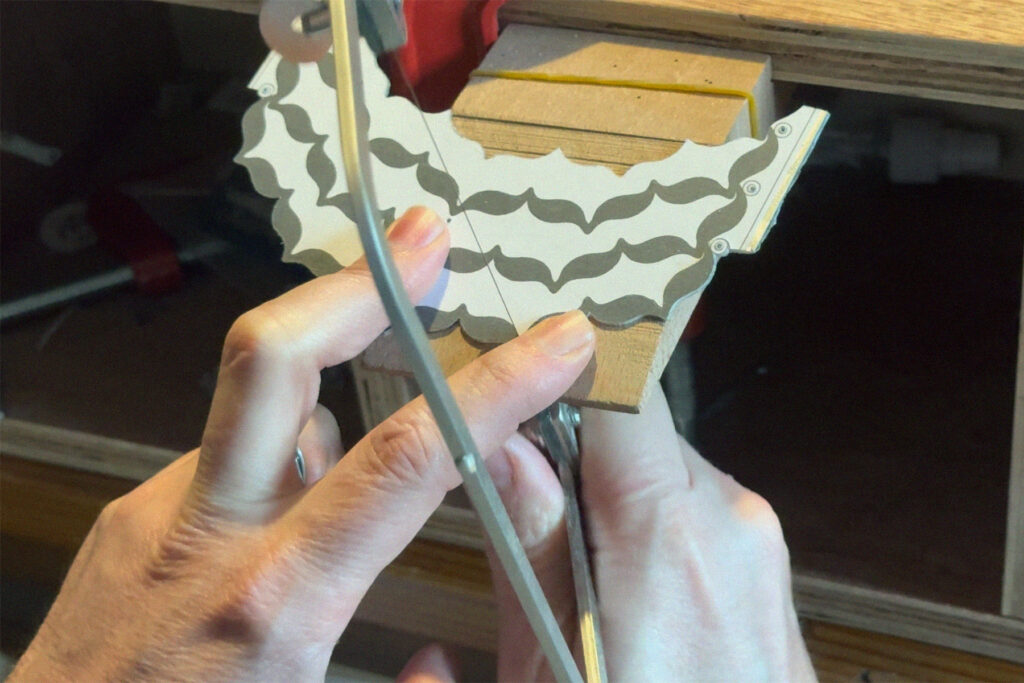

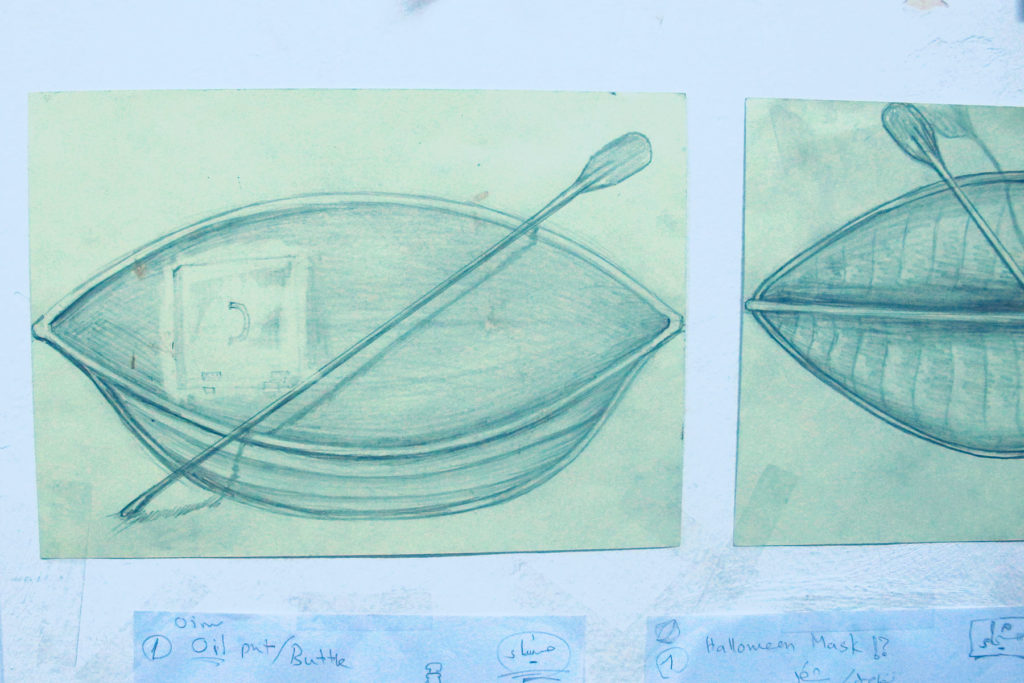

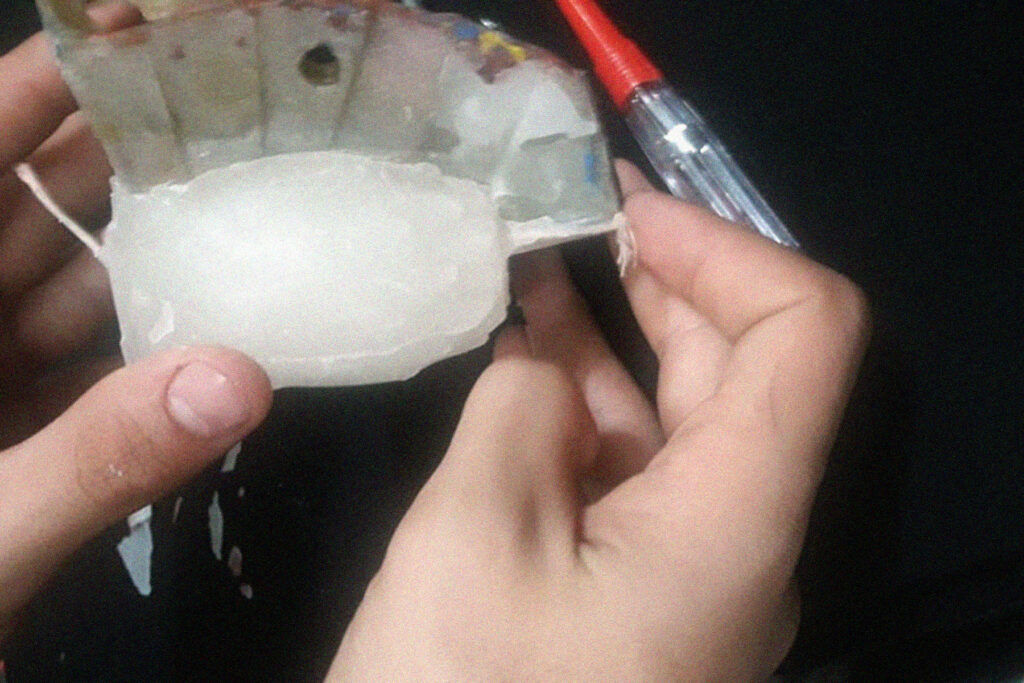

Participants Disarming-Design-workshop, International Academy of Arts Palestine, Ramallah, first day of workshop, August 2012

.

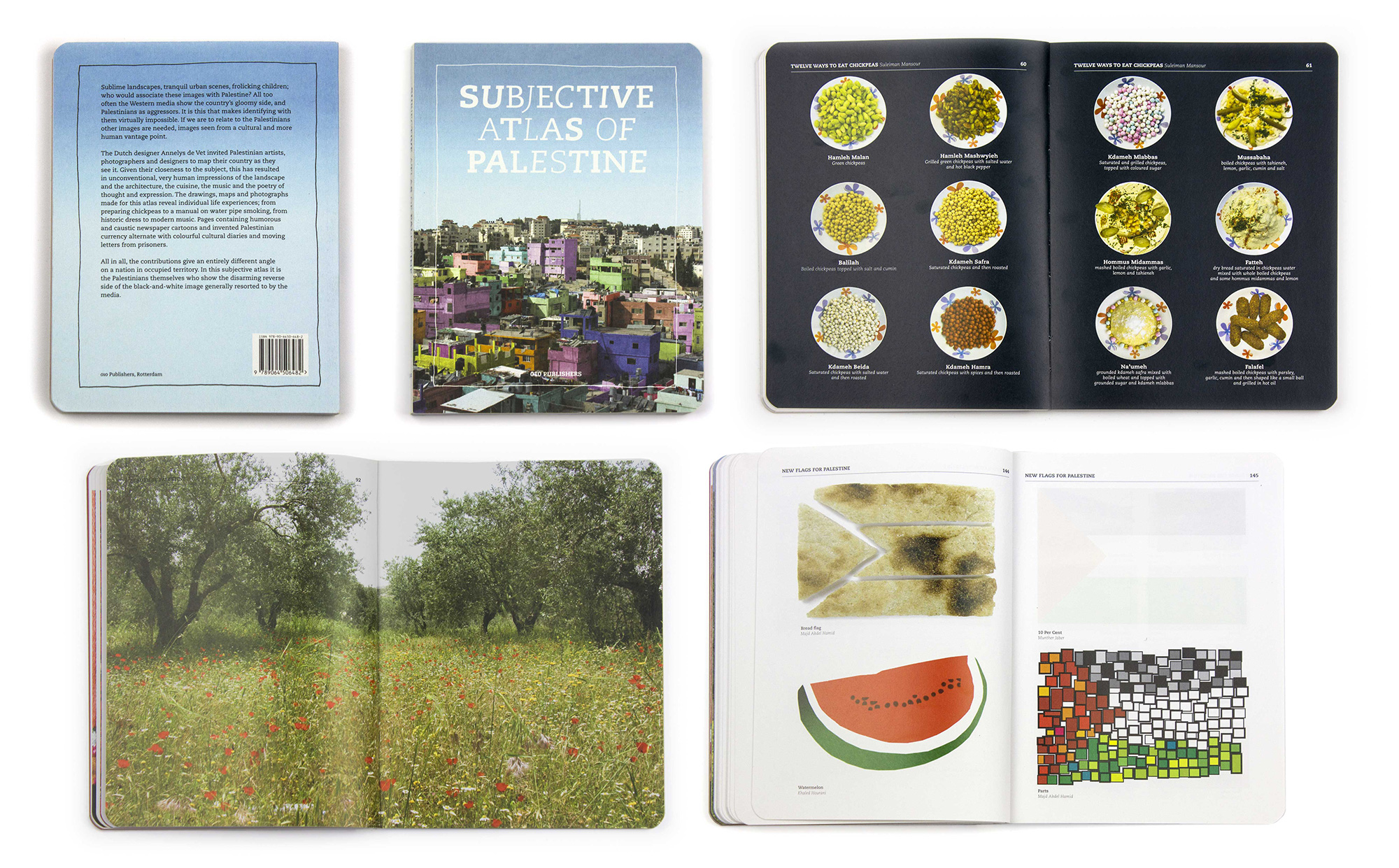

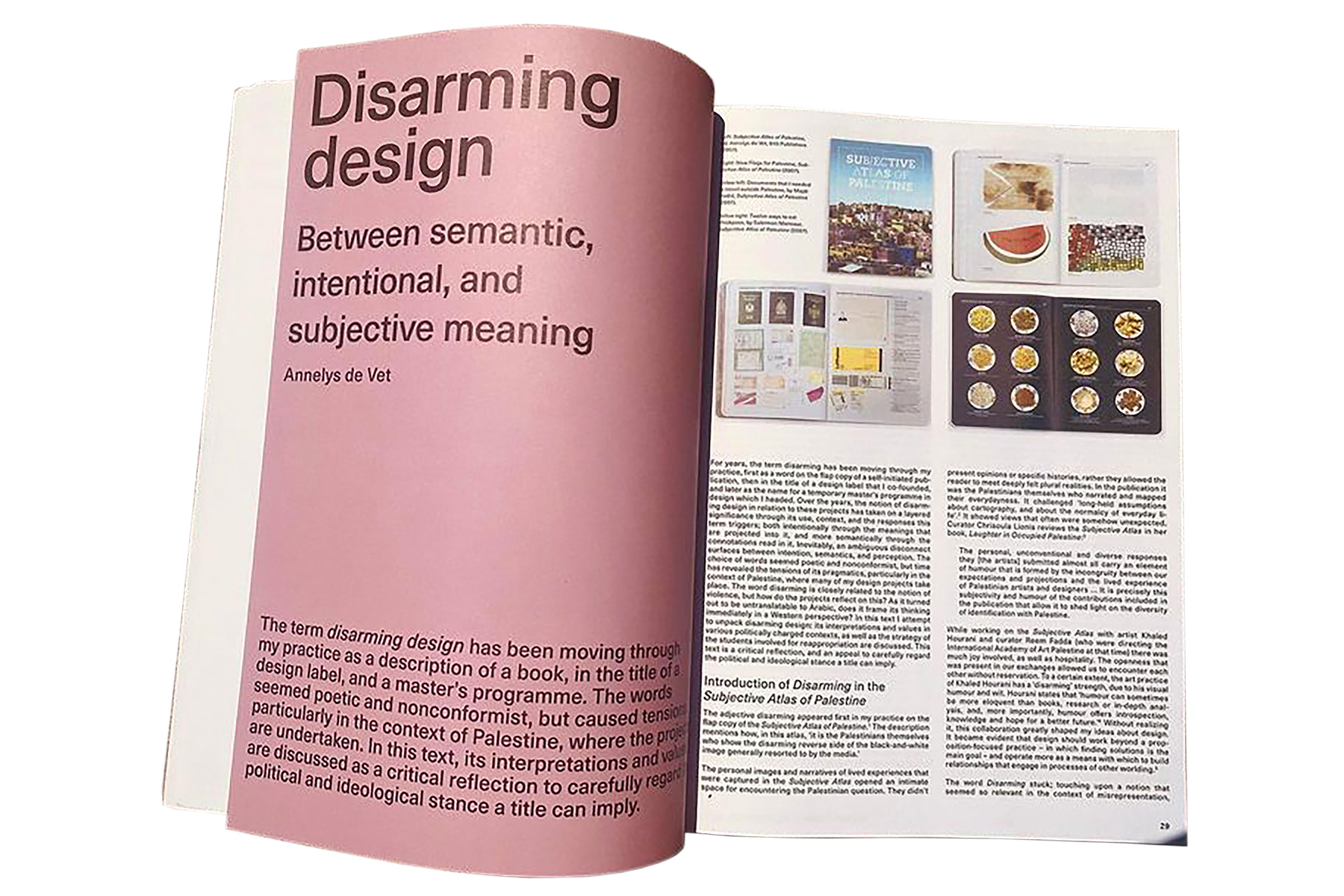

Naming Disarming Design from Palestine

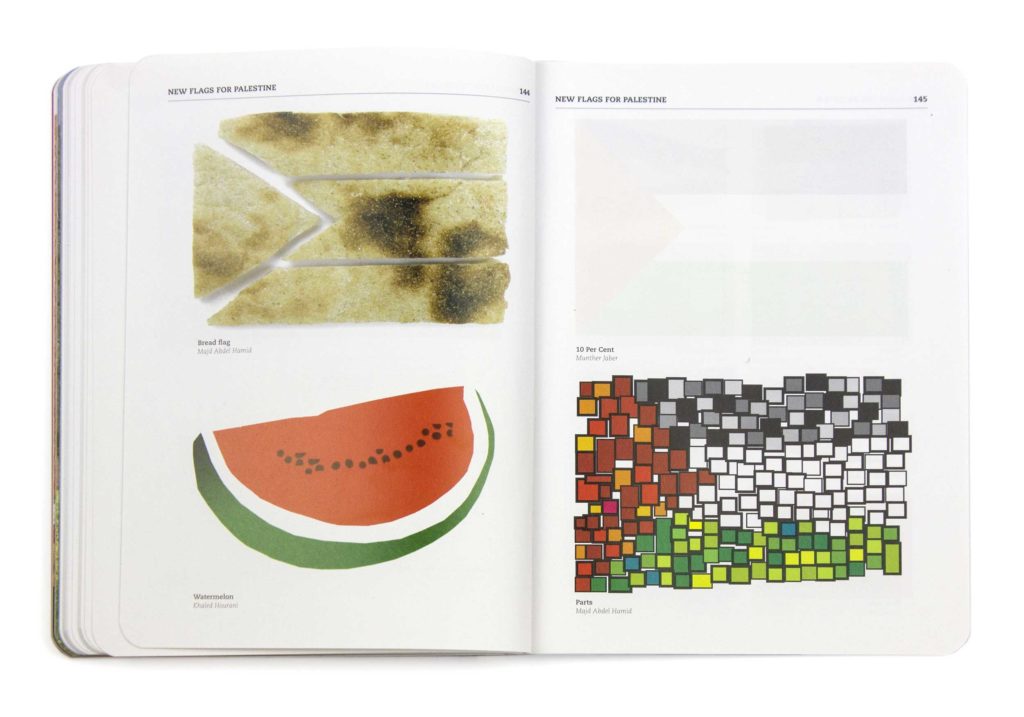

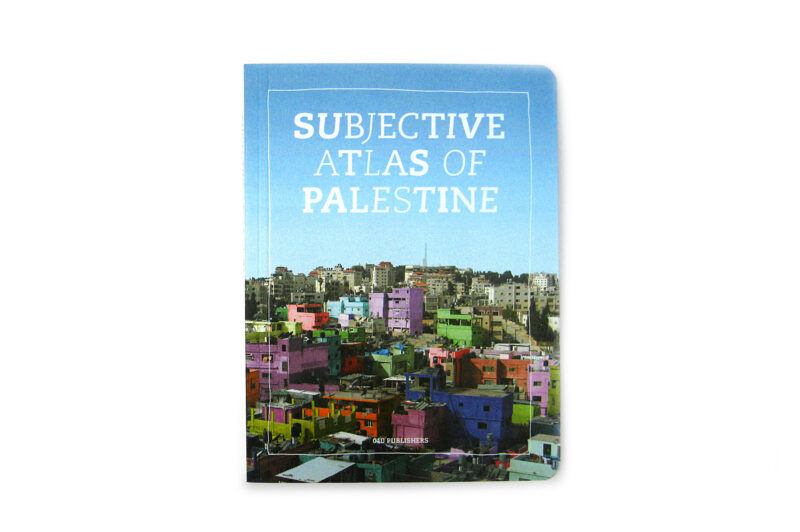

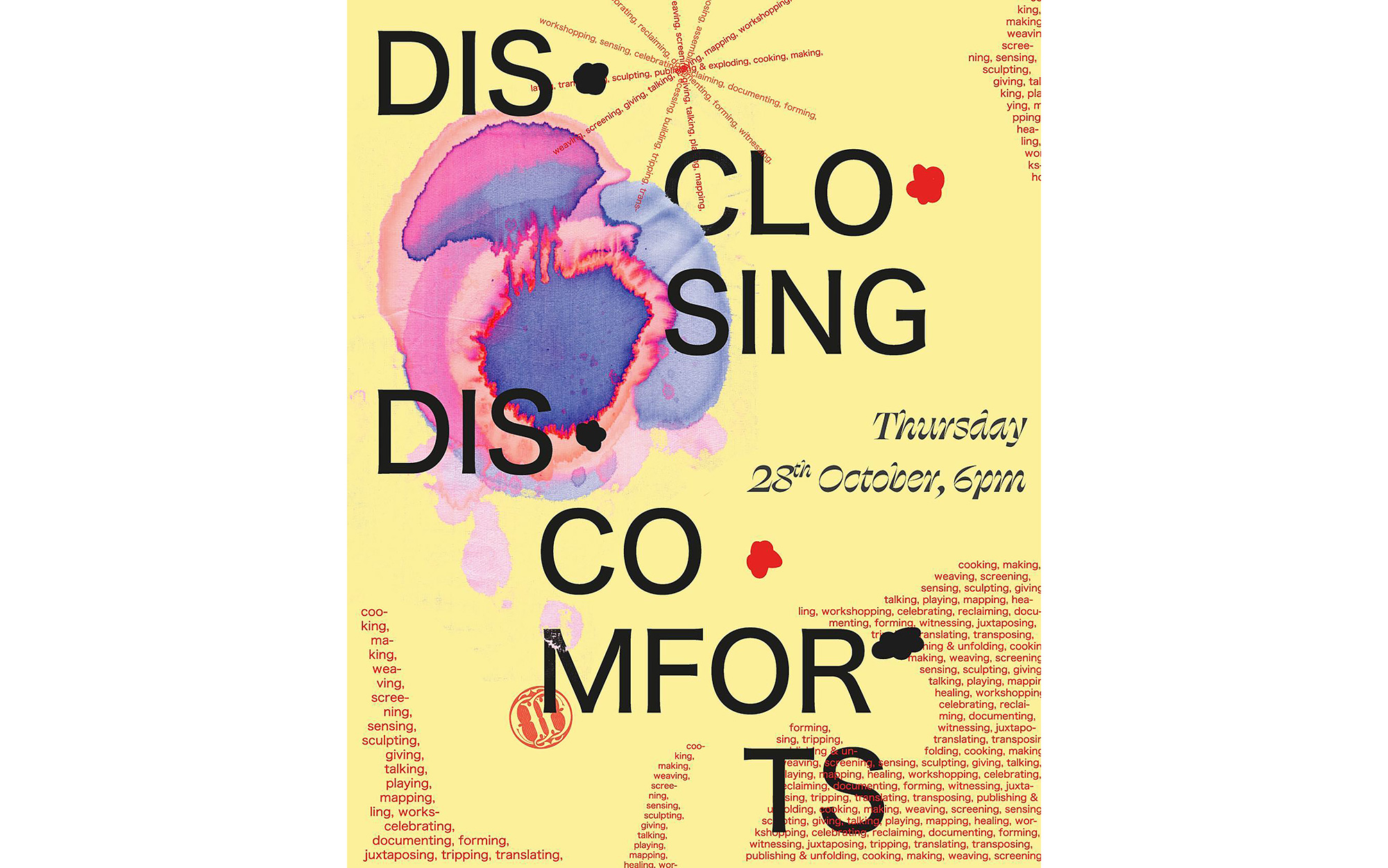

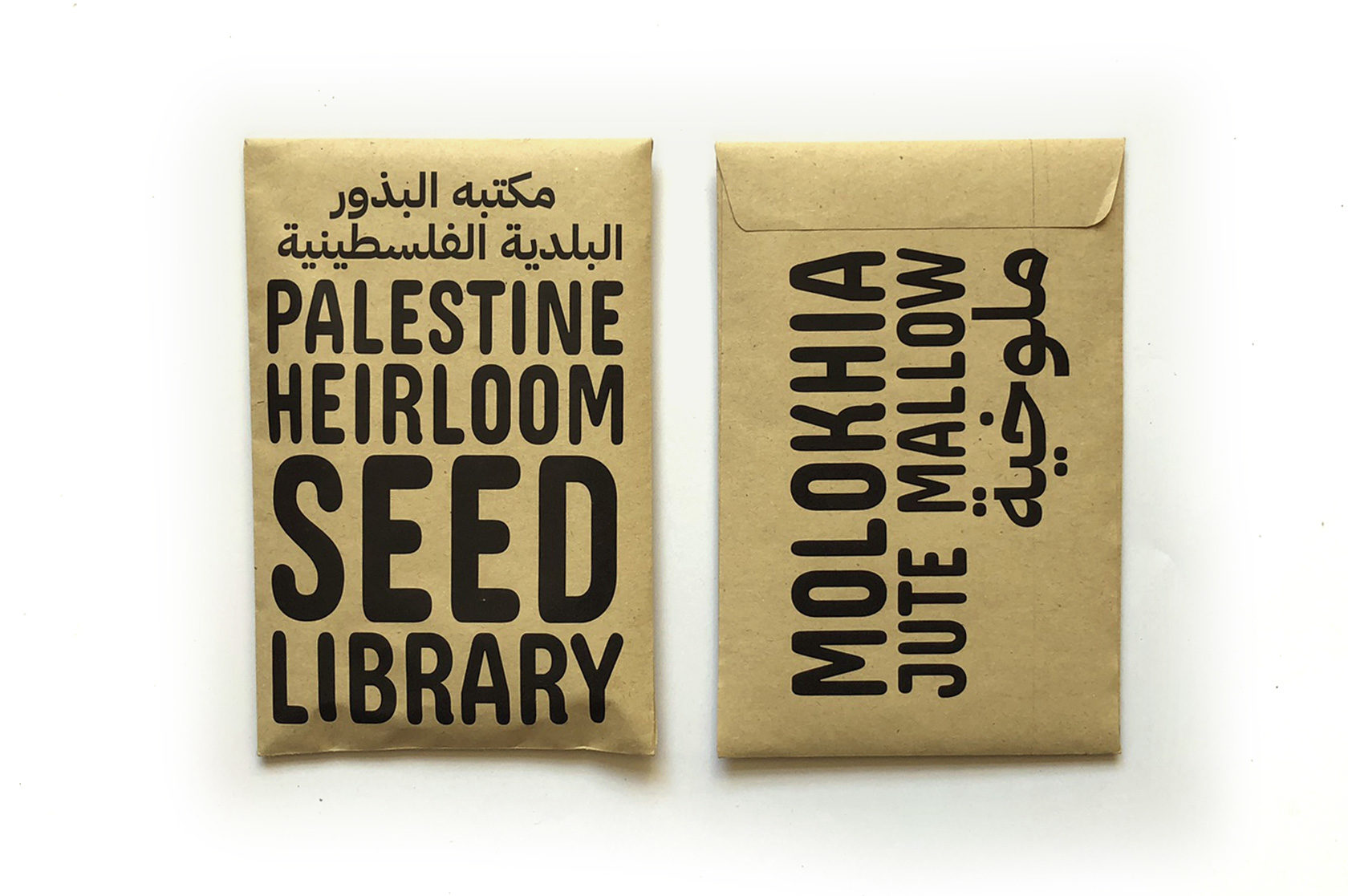

Several years after the Atlas project, in 2012, a new collaborative project emerged. With the International Academy of Arts Palestine (with whom the Subjective Atlas was also developed) we initiated a contemporary design project on local crafts. The aim for this new project was to reach a similar tone of voice as the Subjective Atlas; again ‘personal, unconventional and diverse.’ This time, the materialisation would not take place through alternative cartographies but through useful objects that tell stories. The intention was that we would develop a collection of objects that would invite the user to start conversations about the realities embodied within the products. I suggested titling this imagined design label Disarming Design from Palestine.

Disarming Design from Palestine had a sticky sound as a rhythmic alliteration, it rhymed and was thought-provoking in its plural connotations of the word Disarming. It did not go unnoticed that the differing meanings could also give rise to controversial interpretations and challenging discussions. Particularly in the context of Palestine, it keeps raising questions. I couldn’t decide if using this title was a valid choice, as it had to be carried by all involved. When proposing it to Khaled Hourani, director of the Academy, he smiled; he appreciated the duality of the title and its humour. We tested the name with many people in Ramallah, and asked their opinions. Majd Abdel Hamid, coordinator of the project at that time:

… there is a cultural aspect of language. I like the name. I know what it means. But the problem is that “disarming” always takes you to an idea that something is armed and this proved to be a little controversial when I was talking to and inviting artists. We are still thinking about the title, how to manoeuvre around it, play with the name without creating some kind of controversy of talking about Palestinian design as armed design. (Electronic Intifada, 2012)

Some really appreciated the name, others were a little dazed on hearing the title at first. The fact that it opened conversations and included a sense of poetry convinced most. Hence we decided to call our collaborative project Disarming Design from Palestine.

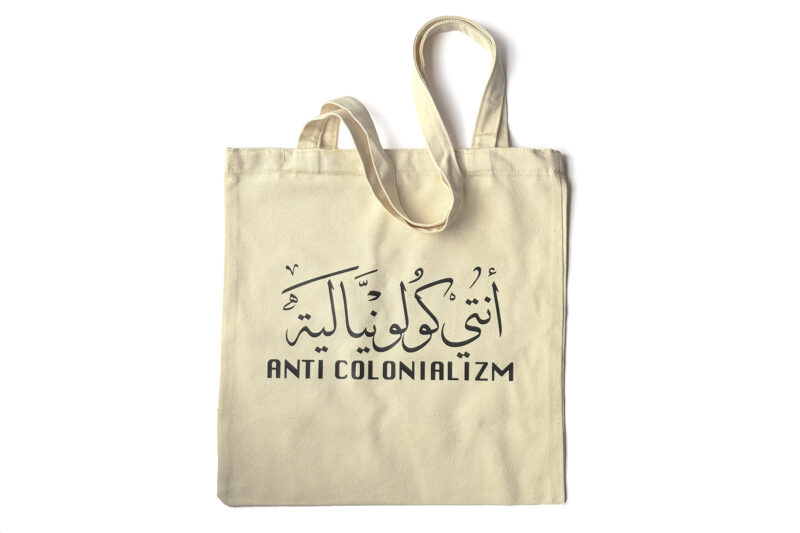

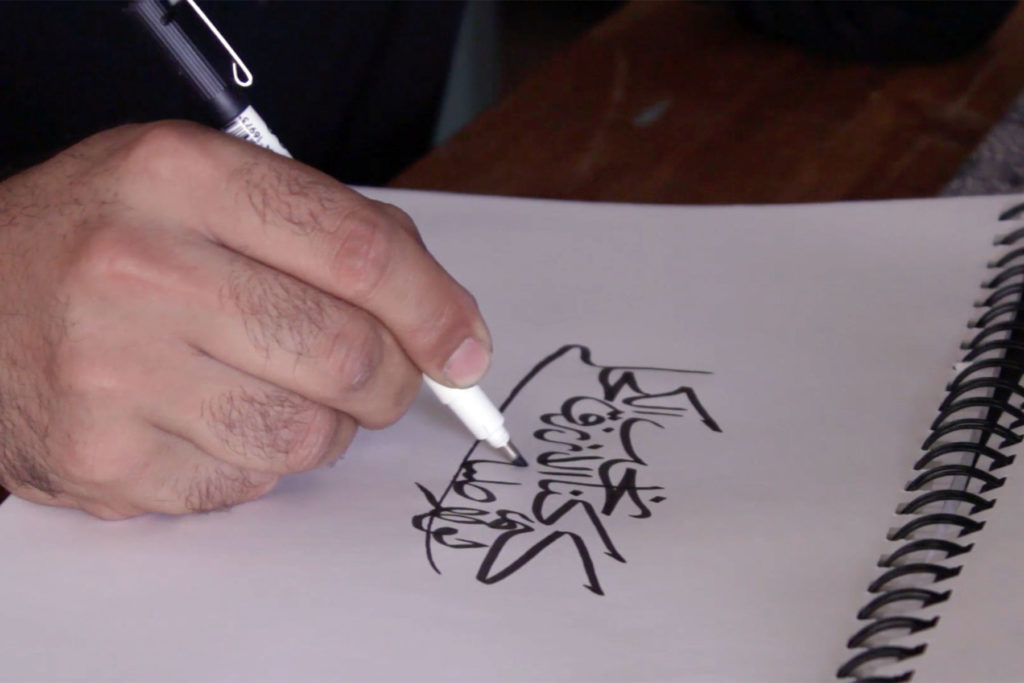

Several European languages have a similar translation to the word disarming, such as Dutch, German, Spanish or French, but it turned out to be untranslatable to Arabic. The literal translation would be نزع سلاح, which means singularly taking away the weapons. There was no other word that would make sense in Arabic and which would have a similar complex of meanings as the adjective disarming. So the first year we translated our project to تصاميم من فلسطين , which just means ‘Designs from Palestine’. But this title was not to the point; our project was not about any design from Palestine, it focused on ethically produced conceptual designs that carried a political message. After many alternatives were rejected, we decided to use the translation as تصاميم مجرّدة من فلسطين, which means something like ‘Abstracted Designs from Palestine’. مجرّدة (mujarrada) comes from the root ‘جرد’ (jarada) which means ‘to strip down’, it becomes abstracted in the sense that all layers are taken off. Perhaps this translation comes most close to disarming as an adjective, but in daily use it doesn’t produce the same message as ‘disarming’ does in European languages. The issue of the difficult translation made clear that the title had a problematic aspect; it derived from the language of the former British coloniser, and that of the lingua franca of the international community flocking into Palestine. It was not a locally rooted term.

It is clear that in the context of Palestine, the notion of disarming is heavily charged. Are we talking about taking away the arms of Palestine or Israel? Should design disarm Palestine or Israel? Should the image of Palestine be disarming, or do the designs spread a disarming message? And disarming who, and what for? In mainstream media, Palestinians are often portrayed as armed even though they are prohibited from being so by the Israeli military occupying powers, who themselves are massively armed. In her 2022 essay “The Arming Act: Reflections on Cultures of Popular Education” (written for the graduation at the master’s programme Disarming Design), architect Saja Amro mentions how to her, the word ‘disarming’ is very negative and frustrating in the context of Palestine:

It triggers me personally. We are a disarmed nation weapon-wise (with both an old and recent shameful history)! There have been constant attempts to disarm the Palestinian popular resistance, while arming the members of the institutionalised Palestinian Authority, which ended up protecting the security of the occupation and preventing any act of resistance against it.

The word disarming in the context of Palestine, is closely related to the notion of violence; disarming as such is what the colonial project of Israel is engaging in, in her struggle to have the monopoly of violence in a settler colonial state. The term connotes a kind of de-politicisation of Palestinian resistance or culture, especially in the association with armed struggle. In a conversation with curator Lara Khaldi she mentions how this makes it problematic:

When it comes to armed resistance in Palestine, in contrast to the situation in the Ukraine for example, the conversation is blocked. This is why in order for our arguments and voices to reach outside, we first “have to be disarmed” in a sense. It needs to be announced that it is peaceful, that it is tamed.

Becoming aware of the different positions regarding the choice of words that composed the project’s title, soon an urge was felt to change it. However, during workshops, exhibitions or events, and sometimes out of the blue, people approached us to mention how ‘brilliant’ they felt the name was—this came both from people within Palestinian and international communities. Many assured us we had to keep the name, and not to propose an alternative. Amidst these conflicting positions, I kept asking the opinions of artisans, designers, artists, scholars in Palestine, and also international curators, translators, visitors and many others who were in solidarity with the Palestinian struggle. For instance Designer Nuno Coelho shared how he feels that the title of the project sheds light on Palestine as a place of creativity. He feels that both the Subjective Atlas of Palestine and the products in this project disarm the one who holds prejudices. It is very disarming in the sense that you just can’t criticise it, it works disarmingly: ‘When something is disarming, you engage.’ Lara Khaldi pointed out how it is about positionality. Depending from which position one speaks, it becomes a position of power; the design object can disarm the other. ‘When you disarm someone it means you leave them without, not only literally arms or weapons, you disarm them of any arguments.’ The fact that it does instigate a discussion or thinking about all of this, is quite interesting on its own, Khaldi adds.

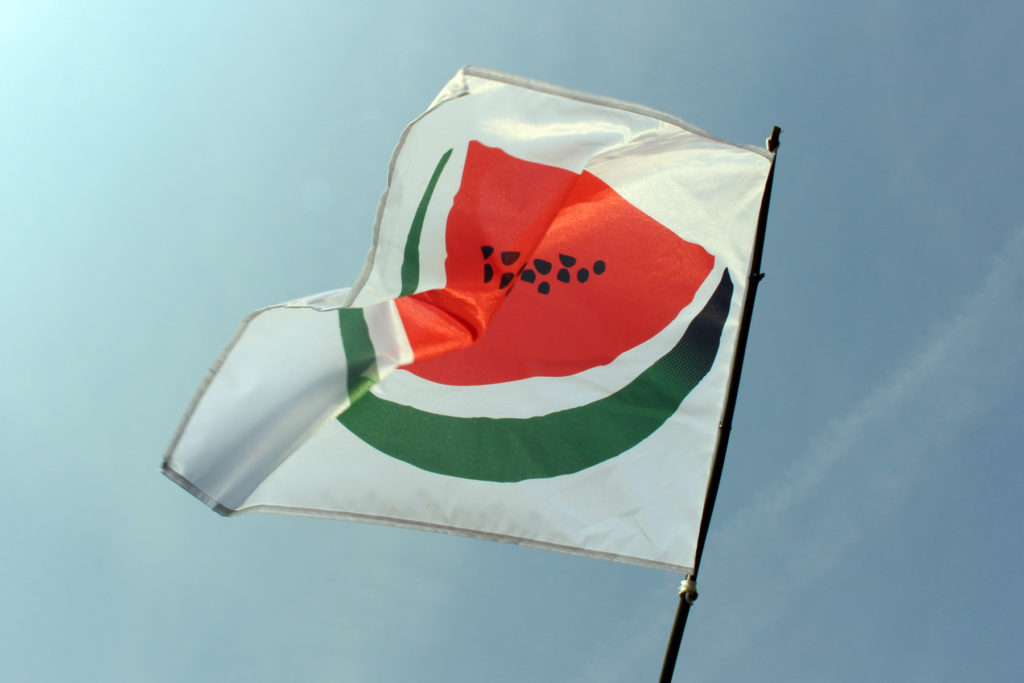

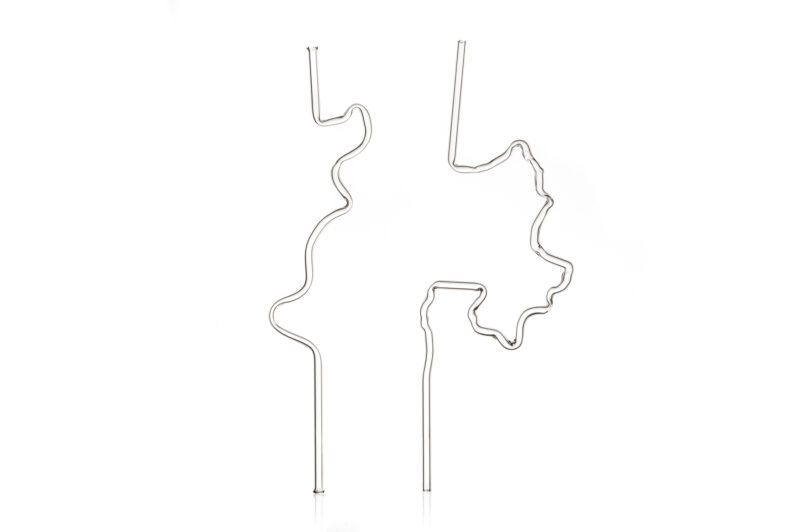

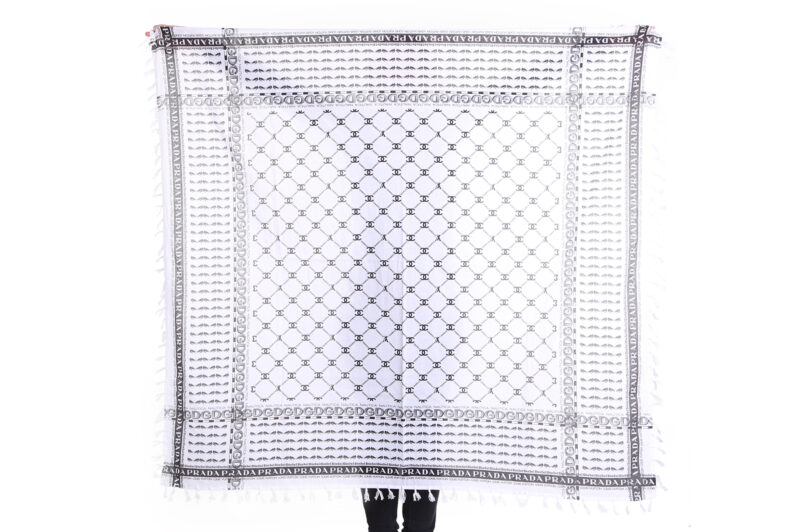

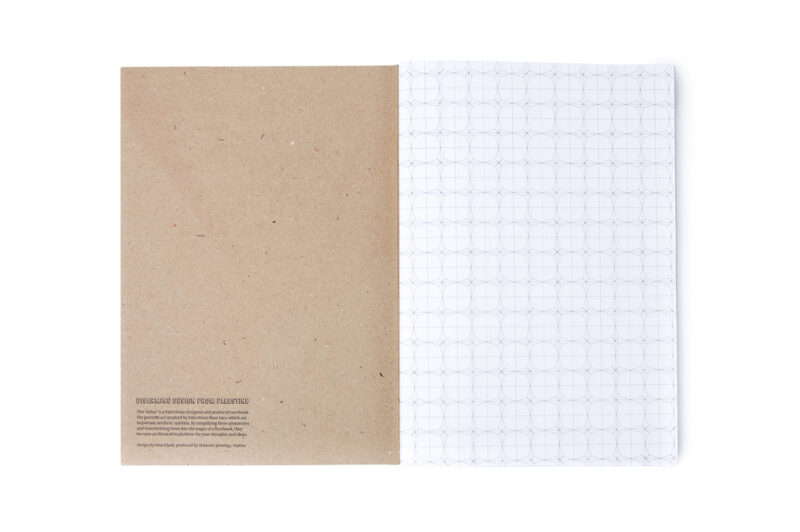

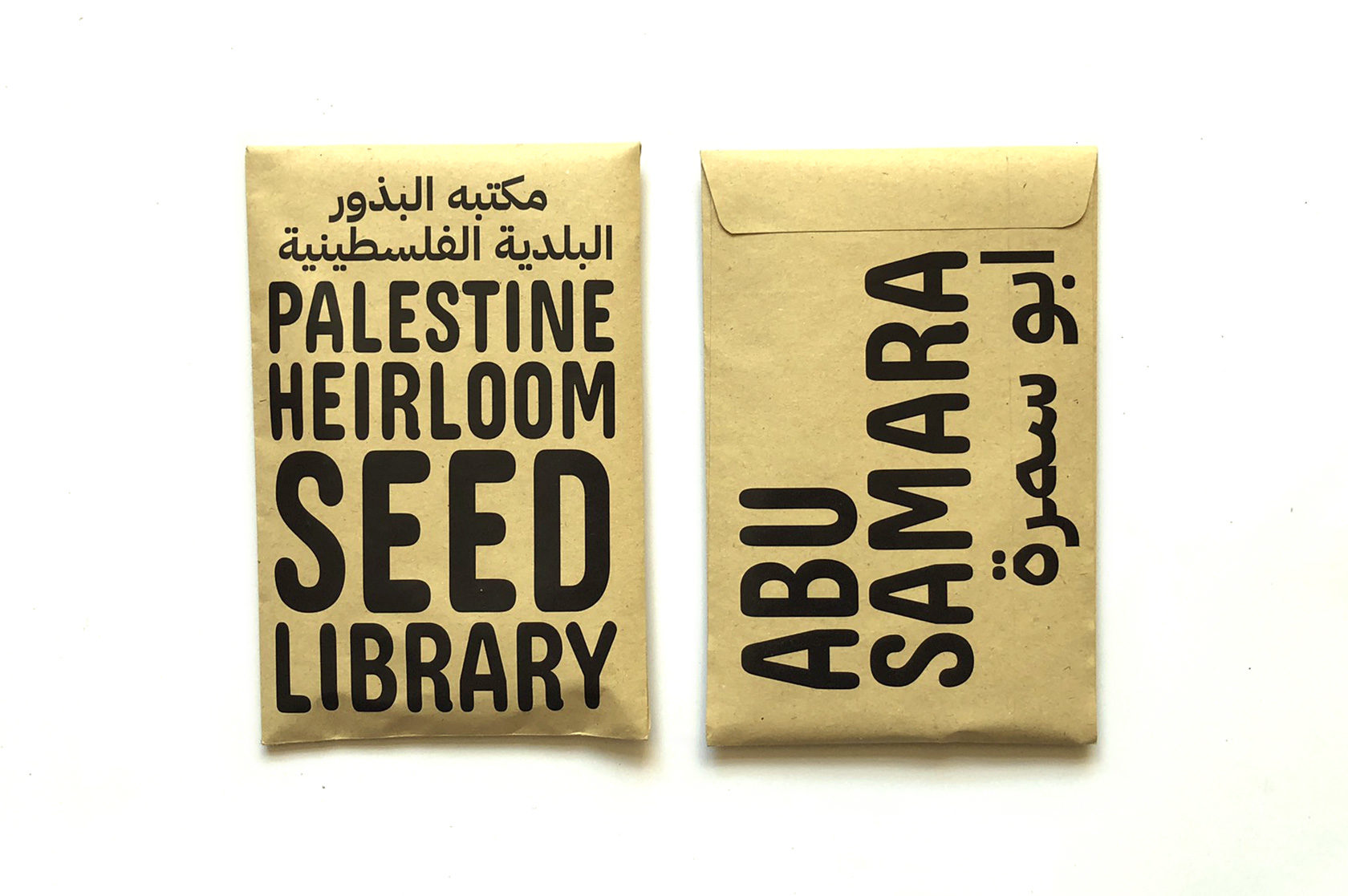

Over time, the meaning of Disarming Design became shaped by the interaction between the title and the designs that were developed under the term. The collection framed the notion of disarming design, which dimmed the question of suitability: the name stuck, resonated and through its repetitive use it worked like a brand. The products it represented, their wittiness and tone of voice, articulated the more contextual meaning. All have a certain thought-provoking aspect, which operates both at the conceptual level (for instance how the title of an item directs its meaning), but also in the kind of clarity and simplicity that each item seems to embody. Each is recognisable as an everyday object (a ceramic plate, a t-shirt, an earring), but through the design—through a certain twist or print or addition—the meaning of the object extends beyond the generalised everyday and touches on another, particular everydayness; the everydayness of living in Palestine. The products are accessible in their commonality but deconstruct reservation and distance because there is something surprising; something that tries to tell a story, that offers a lived perspective that questions the dominant narratives. As objects, they challenge and confront many social and political preconceptions.

The project is a form of cultural resistance and a way to disseminate Palestinian art and design. It foregrounds well-made designs with a presence and narrative; designs that can challenge biases, stimulate critical thinking and trigger reflective moments. As such, the collection uncovers meaningful connections and patterns that can help to both better understand the local heritage and imagine restorative futures. The designs do that through persuading and seducing those engaging with them, sometimes by using humour. As renowned Palestinian revolutionary writer and intellectual Ghassan Kanafani sees it (through the voice of his pseudonym Faris Faris): ‘Humour is not for entertainment and it is not a waste of time, but is an attitude and a commitment at the highest level.’

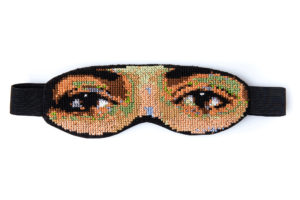

For example the sleeping mask, named Awakening Goggles, has embroidery that depicts the eyes of the artisans in Gaza who made it. When we wear this mask, it looks like their eyes are looking through us or upon us, but we ourselves are blinded. The object sneers at the world turning a blind eye to the ongoing situation in Gaza. It is a well crafted product and is both useful and elegant as a sleeping mask, it connects directly—visually even—with the people who produced the item. Another product is the Proudly Made in Palestine t-shirt, a shirt that looks as though it’s turned inside out, but instead of revealing one label it shows fifteen labels that honour that this t-shirt is ‘Made in Palestine’. Designer Ibrahim Alhindi responds to the local situation where he feels the need to define and clearly show the (re-)development of Palestinian industry. This t-shirt tag is, in many ways, more meaningful than any expressions or phrases printed on the front, and thus what is hidden inside the shirt is more important than its outside appearance.

Another item is the Unveiled Souls bag by Qusai Al Saify. It’s an origami-folded cotton bag that only reveals its hidden beauty when engaged with; underneath the corners of the folded cotton, you find colourful embroidery. The shapes are based on villagers’ patterns and symbolise displaced memories that are stitched together with dedication.

The objects can be seen as cultural tools that defy authority. In that way, items in the collection could be considered as ‘objects of agency’, as designer Danah Abdullah coins this notion in her essay on designing resistance ‘Against Performative Positivity’:

To engage with the world around us and to become design dissenters, we […] should move away from creating instruments of control and into producing objects of agency that pose questions; that are designing alternative forms of political and economic organising.

The collection as a whole forms a voice that speaks beyond each individual object. None of the objects or narratives suggest that we want to dis-arm or de-weaponize the Palestinian resistance. The designs are rooted in anti-colonial resistance and we see them as manifestations of cultural agency. But it took time to clarify this position and to express and build trust with a wider audience. We had to, and still must, speak clearly, politically, about our intentions and our position as a design initiative. This requires careful articulation and framing, but most of all a radical transparency about both intention and methodology.